4. The Bow

Bow making is an entirely distinct art from instrument making - bow makers are very rarely also instrument makers, and vice versa. In fact, when playing at a professional level, it is the bow more than the instrument that is capable of feats of technical magic something most great string players acknowledge. A fine viola is a magnificent thing, but it is essentially a vessel for producing and projecting a beautiful sound. It is the bow that turns that sound into something useable loud, quiet, long, short, smooth, detached and a thousand other gradations besides. A fine bow can do all these things, and move from one to another in a fraction of a second, so when purchasing a viola, it is important not to think of the bow as a relatively unimportant accessory - it needs to chosen with as much care as the instrument itself.

The Frenchman Francois Tourte, working in the early 19th Century, is generally accredited as the father of the modern bow. Having said that, bow making continued to develop throughout the rest of the century, so while Tourte bows are worth tens of thousands of pounds today, they are considered relatively difficult to play by modern standards. Nonetheless, it was Tourte who standardised the overall length, weight and design of the bow, and also pioneered the use of pernambuco as the best wood for the purpose.

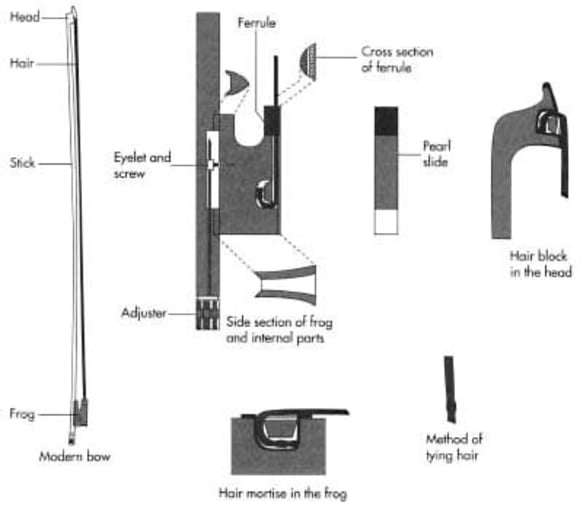

Stick

The stick can be round or sometimes octagonal in section. As with one-piece and two-piece backs, neither signifies higher quality, it is simply a matter of taste on the part of the maker. Pernambuco wood (from the state of Pernambuco in Brazil) is used for the majority of bows by virtue of its immense strength and spring-like flexibility. Although not quite as dense as ebony, it is still barely able to float in water. Brazil wood (something of a poor relation to pernambuco) is often used to make student bows, but the most interesting alternative material is carbon fibre, the use of which is rapidly expanding and is one of the only instances of a modern technology successfully flourishing in the ancient world of string instrument manufacture. While the worlds finest bows are still of wood, carbon fibre makes a good case for itself, both in terms of cost and performance in the low to mid price range. It has the added advantage of being practically indestructible and inert to changes in temperature and humidity.

Frog

The block that is mounted at the held end of the bow is known as the frog and is usually made of ebony (occasionally tortoise-shell or ivory) and inlaid with mother of pearl. Unlike violin bows, most, though not all viola bows, have the rear corner of the frog rounded off as with cello bows. The metal fittings (the screw, the ferrule and occasionally the bow tip) can be of nickel, silver or gold, usually depending on the quality of the bow, and it is by turning the screw at the end of the frog that the hair is either tightened or slackened. When playing, the hair needs to be tight, but it is very important to remember that the sticks natural curve (down towards the hair) should never be lost through over-tightening, let alone forced to bend left or right. When not in use, the bow should always be stored in the case with the hair un-tightened in order to avoid distorting the stick.

Lapping

Lapping is the name given to the binding that covers the stick just before the frog. To a certain extent, it protects the wood from wear, but principally, it is there to ensure a degree of grip for the violists first finger. A variety of materials can be used, most commonly silver or gold wire, but also whalebone (alternate spirals of black and off-white), though these days, it is more likely to be imitated in plastic! The slightly raised pad of leather you can see in the picture is known as the thumb-piece and serves to locate the thumb on the bow without needing to grip the stick tightly.

Hair

Famously sourced from the tails of horses, it is the hair that literally draws the sound out of the instrument. Put it under a microscope and youll see that each strand is covered in tiny barbs it is these that cause the strings of the instrument to vibrate when the bow is drawn across them. White hair is the most desirable due to its greater fineness which produces a smoother, fuller sound. For complete beginners, it is acceptable to use darker or mixed hair, but once beyond the very earliest stages of learning, it is best to have bows re-haired in white.

Din kontaktperson

Produkthighlights

Erbjudanden

-

3/4 fiol

-

1/2 fiol

-

1/4 fiol

-

1/8, 1/10 och 1/16 fioler

-

Akustisk violin/fiol